Interview

Taylor Made

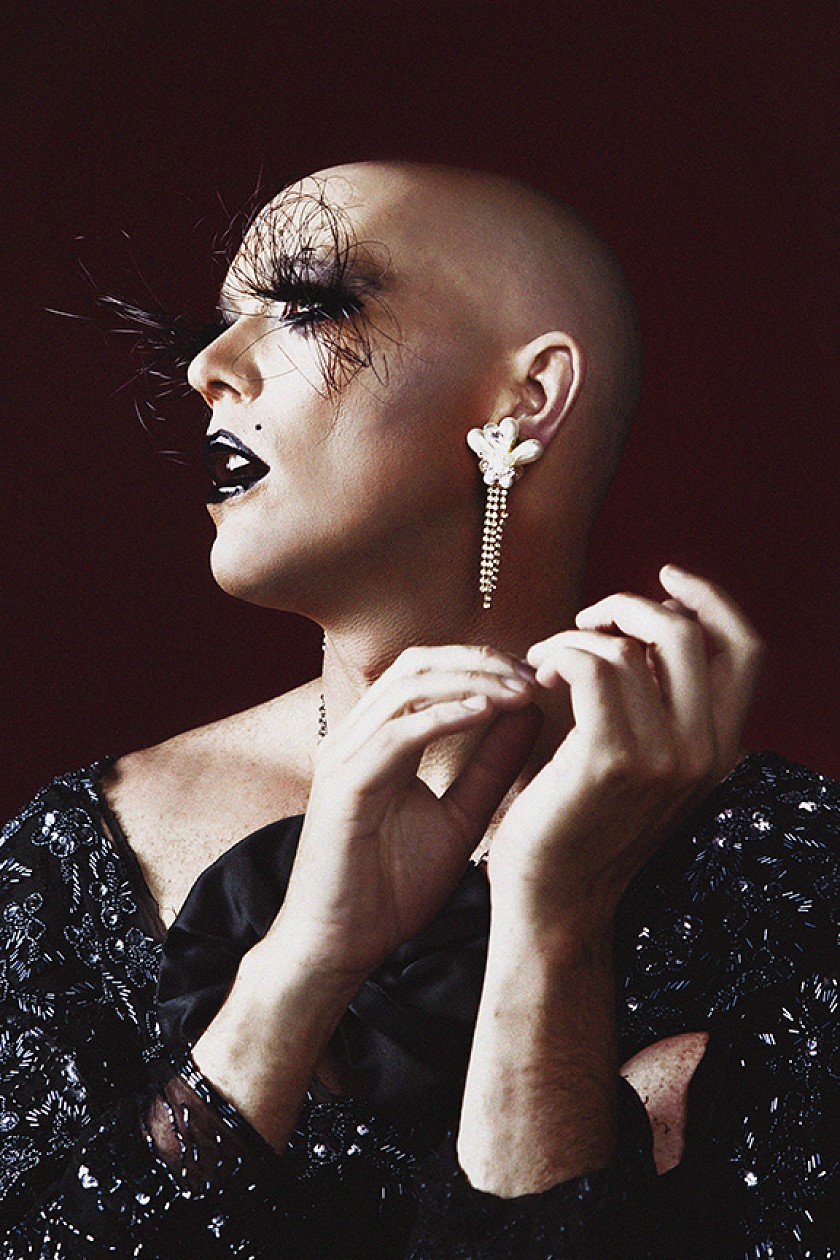

It was just announced that Taylor Mac’s 24 DECADE HISTORY OF MUSIC will open the 2016/2017 season of St. Ann’s Warehouse in September. But Mac first stopped off at the Curran a few months ago to perform six hours of the show and talked to us about life, liberation, and Liberace.

THE CURRAN[T]: You have said that your work is all about healing. So is the 24 DECADE HISTORY OF POPULAR MUSIC finally about healing?

TAYLOR MAC: To some degree. Yeah. But it’s also a Radical Faerie realness ritual.

Don’t you have a decade or two dedicated to the Radical Faeries?

I think I might have already gotten rid of that. I have a radical lesbian one now. Everything is changing. Everything is evolving.

See? You’re healing.

Since the whole thing is a Radical Faerie realness ritual I didn’t have to focus just one decade on that.

Explain it a bit more for those who don’t readily know what a Radical Faerie realness ritualistic aesthetic is.

It is the history of popular music in the United States—not necessarily music that was written here but was popular here. It goes from 1776 to 2016. It is exactly 240 years. 24 decades. We do an hour for every decade. There are eight acts of three hours each and those acts are now beginning to be performed on their own. In August we are going to combine four of them and do a twelve hour show. But we’ll only do a 24-hour show once. That will be in the fall of 2016. When we do the 24-hour show there won’t be any intermissions. But there aren’t any intermissions in the three-hour shows either.

Do you take bathroom breaks yourself? If not, then that is real performance art on your part.

The thing is I never leave the stage. There are instrumental interludes. I do go behind a scrim for costume changes and things or I’ll go to the bathroom behind the scrim. We are going to experiment with all the different ways I can take a bathroom break while doing the show.

Your first performances in San Francisco will be the first act which focuses on revolutionary times in America. During the second week of your stand at the Curran you’re doing Act Two which is described as “Recovery from Revolution,” which sounds as if it is about healing from upheaval.

Well, it still has a little bit to do about that but it’s really now about songs that were popular with housewives of that time. So it’s songs that were popular with women when the feminist movement was just beginning. Right after the Revolutionary War women began to see that there was all this talk about freedom and man being free. They began to think of freedom for themselves and began to articulate that. There was a remarkable woman during that time named Judith Sargent Murray who wrote an essay titled “On the Equality of the Sexes”—a kind of feminist manifesto—that predates Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. There was this kind of theme that was happening of women trying to get their equal rights. And it still hasn’t happened.

That is what is interesting about this work. We’ll start a theme in the 1780s and then we’ll touch base with it again in the 1870s and then yet again in the 1910s and then we’ll touch base with it again in the 1990s. It really shows this onslaught of history and how we make so many excuses to hold ourselves back and not make the change that is demanded of us. So this is how the show is about healing. It gives the audience an opportunity to recognize the things we are forgetting or dismissing or burying—or that other people have buried for us—and to say that this is not serving us anymore - this trope—or this tradition or this social dictate—therefore let’s sacrifice it. It’s basically having a ritual sacrifice of the things that are keeping us back. Throughout the decades we are focusing on something we could let go of that we are still holding onto as a culture.

“A lot of people wear costumes to use it as a mask. But I use it as something to reveal myself. What I am doing is that I am showing a part of myself onstage that I normally would not show. The outfits for me are an expression of what I look like on the inside.”

As you were putting the show together, which was more important to you when choosing the songs that you perform—that they be good and entertaining and have a theatrical life or that they feed into this overarching concept of the show regardless of their quality as songs?

It’s a little “yes and …” First of all I was looking for songs that were trying to reach the people. What were the songs that were attempting to galvanize the people to do something? I think when people are performing a piece of classical music they are trying briefly to touch the hem of God. They are reaching for perfection. But a popular song is written to reach the people. Most popular songs that have stuck around for a while are trying to do specific things—rally people to a cause, get them to celebrate together, mourn together, recognize love together. Then there is the other criterion: does it fit with my theme. I don’t worry about it being good or bad.

How do you dig this stuff out? What are your resources? We weren't even aware there was such a thing as “popular music” during the periods you are highlighting during your Curran run: 1776 - 1836.

If I were doing this show even fifteen years ago, it would have been extremely difficult. I would have had to write a grant, travel around to all the libraries, and meet with all the higher musicologists and convince them to work with me. But most of this is now online.

This could be perceived as a stunt. It does have a stunt-like quality to it. How do you combat that artistically?

Well, you could say that about anything. Death of a Salesman could be very stunt-like. It could be a gimmick—a man is going crazy a little bit and is remembering his past. It’s all about what you do with it that changes it.

And what was the catalyst to take on such a giant ritualistic undertaking as this?

That goes back to 1986. I was living in Stockton. I had never met an out homosexual before—or, at least, one that was out to me. I found out about this AIDS Walk that was happening in San Francisco so I went with my friend Marcie. The first time I ever saw an out homosexual was thousands of them at the same time. It was a profound experience to see that queer history, queer agency, queer pride, queer power all for the first time.

And queer grief.

Yes. Queer grief. People were pushing loved ones in wheelchairs. The Sisters of Perpetual of Indulgence were there. I saw my first drag queens that day.

How old were you?

Fourteen or fifteen. People were singing and chanting. People were screaming and furious. ACT UP was there. It was the first AIDS Walk they ever had I think in San Francisco before it became something one was expected to attend. So that first one felt like a seditious act just to be there.

There were no corporate floats.

Or corporate t-shirts. To discover that community as a result of the community deteriorating and falling apart because of the epidemic was to discover at the same time a community being built and strengthened. That paradox—the dichotomy of that—was profoundly interesting to me and I think I just put that in the back of my brain. No. It didn’t go to the back of my brain. It was one of the most profound moments of my life and really affected me. Fast forward 30 years later and I wanted to make a show that was a metaphor and a representation of that. I wanted to put the audience in a situation in which they are under some kind of complicated circumstance and I’m under some sort of complicated circumstance and as a result of falling apart together we’re building bonds. So I decided to make a durational concert. We could never do it perfectly. Perfection could never be the goal. But reaching the people would be the goal. What has happened is that it is not just a 24-hour durational piece since we haven’t even done that yet but a multi-year durational piece because we’ve been working on it for four years now. Each performance is also a rehearsal. We’ve created a serial essentially, one that people return to over and over -and over the years the audience members are forming a real community. They are getting to know each other. Businesses have started. People have gotten engaged who met at the show. Babies have been born. We have created something tangible from an ephemeral art form.

A lot of your work is about incongruity as well as healing. You are performing centuries-old songs in the segment of the cycle you are doing at the Curran and yet you are giving them a modernist, deconstructive spin.

It’s all subjective. It’s not the 24-decade history of popular music but a 24-decade history. It is my point of view. I call these shows performance art concerts.

You’ve used the word “queer.” Is it a queer perspective you’re bringing to this history?

Well, I am queer so yes it is.

Most popular songs that have stuck around for a while are trying to do specific things—rally people to a cause, get them to celebrate together, mourn together, recognize love together.

Your costuming is so over-the-top that you could be considered our post-modern Liberace.

Well, hallelujah.

There is an outrageousness to the costuming you engage in that is another element of the incongruity. There is such artifice to the costuming and yet such a fierceness to the reality that is being filtered through that costume. How does the audience get past the visual artistry of the costumes—designed magnificently by Machine Dazzle—to arrive at the art of the performance?

A lot of people wear costumes to use it as a mask. But I use it as something to reveal myself. What I am doing is that I am showing a part of myself onstage that I normally would not show. Today I am sitting here with you in a cafe on Irving Place in New York City and I am wearing relative man drag.

The photos of you at the opening night of your play Hir at Playwrights Horizons were shocking. You were wearing a suit and tie. Truly: shocking.

That was my opening-on-42nd-street-A.R. Gurney-is-sitting-next-to-me drag. That was me hiding something about myself. When I’m onstage I want to expose myself. You want to expose the thing that you don’t normally show. So the outfits for me are an expression of what I look like on the inside. That is what I’m telling people when I wear them. It’s more about a risk than it is about a protection.

Do you do any “blackface” when you come upon minstrel songs?

No, no, no. God no.

So there are lines that you won’t cross.

Yes. I don’t think I’d ever do that. But Machine Dazzle does do dress and clothing appropriation with his outfits so that is part of the conversation that is on the stage. When we do the Jewish tenement section of the cycle he has me in giant hoop earrings that look like payos.

But is that not a form of “blackface”? Can costuming itself when exaggerated like that become, in its interpretive overstatement, just a substitute for cultural “blackface”?

I wouldn’t say that is “blackface” because “blackface” to me is a white person’s invention of a culture—not an interpretation of a culture. That is very different than taking something that is and exaggerating it to incorporate it into a story you’re telling. That’s someone else’s 24-decade history if they use “blackface.” I didn’t grow up with anything queer talked about when I was taught history. So I am definitely looking for a queer story. So I have to be very aware of that. Look, if you wanted to, you could do a whole history of popular music in America and the whole thing could be a minstrel song.

And what is a minstrel song to you?

I don’t know what Webster’s definition of it is. But to me it is a song that is written and performed in order to sentimentalize our history, in order to make the performer and the listener so young that nothing is their fault and to take them to a place where innocence exists even though it is the most violent of the art forms because it is such a lie.

You prefer the gender pronoun “judy” when someone writes about you. Garland aside, should we think of Carne when we do so? Or Canova? Or Collins?

All of the above.

That sort of sums you up, Taylor: all of the above.

That’s gorgeous. Yes: all of the above. I am a maximalist—which includes minimalism.

TAYLOR MAC will perform his 24 Decades of Popular Music in it's entirety in four Chapters at the Curran this September 15-24th. Get your tickets for this extravaganza today!